This compilation is for anyone interested about Bhikkhus (monks) and about how to relate to them. Some may think that this lineage follows an overly traditionalist approach but then, it does happen to be the oldest living tradition. A slight caution therefore to anyone completely new to the ways of monasticism, which may appear quite radical for the modern day and age. The best introduction, perhaps essential for a true understanding, is meeting with a practising Bhikkhu who should manifest and reflect the peaceful and joyous qualities of the Bhikkhu’s way of life.

The Discipline of a Buddhist monk is refined and is intended to be conducive to the arising of mindfulness and wisdom. This code of conduct is called the Vinaya. While it is not an end in itself, it is an excellent tool, which can be instrumental in leading to the end of suffering.

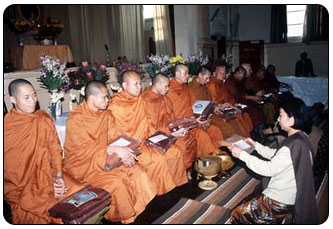

Apart from the direct training that the Vinaya provides, it also establishes a relationship with lay people without whose co-operation it would be impossible to live as a monk. A monk is able to live as a mendicant because lay people respect the monastic conventions and are prepared to help to support him. This gives rise to a relationship of respect and gratitude in which both layperson and monk are called upon to practise their particular life styles and responsibilities with sensitivity and sincerity.

Many of the rules of discipline were developed specifically to avoid offending lay people or giving rise to misunderstanding or suspicion (for example, the rules stipulating that another male be present when a monk and a woman would otherwise be alone together). As no monk wishes to offend by being fussy and difficult to look after, and no lay Buddhist would wish to accidentally cause a monk to compromise the discipline, this booklet is therefore intended to be a useful guide to the major aspects of the Vinaya as it relates to lay people.

Providing the Means for Support

The Vinaya, as laid down by the Buddha, in its many practical rules defines the status of a monk as being that of a mendicant. Having no personal means of support is a very practical means of understanding the instinct to seek security; furthermore, the need to seek alms gives a monk a source of contemplation on what things are really necessary. The four requisites, food, clothing, shelter and medicines, are what lay people can offer as a practical way of expressing generosity and appreciation of their faith in belonging to the Buddhist Community. Rather than giving requisites to particular monks whom one likes and knows the practising Buddhist learns to offer to the Sangha as an act of faith and respect for the Sangha as a whole. Monks respond by sharing merit, spreading good will and the teachings of the Buddha to all those who wish to hear, irrespective of personal feelings.

Food

A monk is allowed to collect, receive and consume food between dawn and midday (taken to be 12 noon). He is not allowed to consume food outside of this time and he is not allowed to store food overnight. Plain water can be taken at any time without having to be offered. Although a monk lives on whatever is offered, vegetarianism is encouraged.

A monk must have all eatables and drinkables, except plain water, formally offered into his hands or placed on something in direct contact with his hands. In the Thai tradition, in order to prevent contact with a woman, he will generally set down a cloth to receive things offered by women. He is not allowed to cure or cook food except in particular circumstances.

In accordance with the discipline, a monk is prohibited from eating fruit or vegetables containing fertile seeds. So, when offering such things, a layperson can either remove the seeds or make the fruit allowable slightly damaging it with a knife. This is done by piercing the fruit and saying at the same time ‘Kappiyam bhante’ or ‘I am making this allowable, Venerable Sir’ (the English translation). It is instructive to note that, rather than limiting what can be offered, the Vinaya lays emphasis on the mode of offering. Offering should be done in a respectful manner, making the act of offering a mindful and reflective one, irrespective of what one is giving.

Clothing

Forest monks generally make their own robes from cloth that is given. Plain white cotton is always useful (it can be dyed to the correct dull ochre). The basic ‘triple robe’ of, the Buddha is supplemented with sweaters, tee-shirts, socks, etc. and these, of an appropriate brown colour, can also be offered.

Shelter

Solitary, silent and simple could be a fair description of the ideal lodging for a monk. From the scriptures it seems that the general standard of lodging was to neither cause discomfort nor impair health, yet not to be indulgently luxurious. Modest furnishings of a simple and utilitarian nature were also allowed, there being a rule against using ‘high, luxurious beds or chairs’, that is, items that are opulent by current standards. So a simple bed is an allowable thing to use, although most monks prefer the firmer surface provided by a mat or thick blanket spread on the floor.

The monk’s precepts do not allow him to sleep more than three nights in the same room with an unordained male, and not even to lie down in the same sleeping quarters as a woman. In providing a temporary room for a night, a simple spare room that is private is adequate.

Medicine

A monk is allowed to use medicines if they are offered in the same way as food. Once offered, neither food nor medicine should be handled again by a layperson, as that renders it no longer allowable. Medicines can be considered as those things that are specifically for illness; those things having tonic or reviving quality (such as tea or sugar); and certain items which have a nutritional value in times of debilitation, hunger or fatigue (such as cheese or non-dairy chocolate).

Sundries

As circumstances changed, the Buddha allowed monks to make use of other small requisites, such as needles, a razor, etc. In modern times, such things might include a pen, a watch, a torch, etc. All of these were to be plain and simple, costly or luxurious items being expressly forbidden.

Invitation

The principles of mendicancy forbid a monk from asking for anything, unless he is ill, without having received an invitation. So when receiving food, for example, a monk makes himself available in a situation, where people wish to give food. At no time does the monk request food. This principle should be borne in mind when offering food; rather than asking a monk what he would like, it is better to ask if you can offer some food. Considering that the meal will be the only meal of the day, one can offer what seems right, recognising that the monk will take what he needs and leave the rest. A good way to offer is to bring bowls of food to the monk and let him choose what he needs from each bowl.

Tea and coffee can be offered at any time (if after noon, without milk). Sugar or honey can be offered at the same time to go with it.

One can also make an invitation to cover any circumstances that may arise which you may not be aware of by saying, for example, ‘Bhante, if you need any medicine or requisites, please let me know’. To avoid any misunderstanding, it is better to be quite specific about what you are offering. Unless specified, an invitation can only be accepted for up to four months, after which time it lapses unless renewed.

Inappropriate Items Including Money

T.V.’s and videos for entertainment should not be used by a monk. Under certain circumstances, a Dharma video or a documentary programme may be watched. In general, luxurious items are inappropriate for a monk to accept. This is because they are conducive to attachment in his own mind, and excite envy, possibly even the intention to steal, in the mind of another person. This is unwholesome Kamma. It also looks bad for an alms mendicant, living on charity as a source of inspiration to others, to have luxurious belongings. One who is content with little should be a light to a world where consumer instincts and greed are whipped up in people’s minds.

Although the Vinaya specifies a prohibition on accepting and handling gold and silver, the real spirit of it is to forbid use and control over funds, whether these are bank notes or credit cards. The Vinaya even prohibits a monk from having someone else receive money on his behalf. In practical terms, monasteries are financially controlled by lay stewards, who then make open invitation for the Sangha to ask for what they need, under the direction of the Abbot. A junior monk even has to ask an appointed agent (generally a senior monk or Abbot) if he may take up the stewards’ offer to pay for dental treatment or obtain medicines, for example. This means that as far as is reasonably possible, the donations that are given to the stewards to support the Sangha are not wasted on unnecessary whims.

If a layperson wishes to give something to a particular monk, but is uncertain what he needs, he should make an invitation. Any financial donations should not be to a monk but to the stewards of the monastery, perhaps mentioning if it’s for a particular item or for the needs of a certain monk. For items such as travelling expenses, money can be given to an accompanying anagarika (dressed in white) or accompanying layperson, who can then buy tickets, drinks for a journey or anything else that the monk may need at that time. It is quite a good exercise in mindfulness for a layperson to actually consider what items are necessary and offer those rather than money.

Relationships

Monks and nuns lead lives of total celibacy in which any kind of sexual behaviour is forbidden. This includes even suggestive speech or physical contact with lustful intent, both of which are very serious offences for monks and nuns. As one’s intent may not always be obvious (even to oneself), and one’s words not always guarded, it is a general principle for monks and nuns to refrain from any physical contact with members of the opposite sex. Monks should have a male present who can understand what is being said when conversing with a lady, and a similar situation holds true for nuns.

Much of this standard of behaviour is to prevent scandalous gossip or misunderstanding occurring. In the stories that explain the origination of a rule, there are examples of monks being accused of being a woman’s lover, of a woman’s misunderstanding a monk’s reason for being with her, and even of a monk being thrashed by a jealous husband!

So, to prevent such misunderstanding, however groundless, a monk has to be accompanied by a man whenever he is in the presence of a woman; on a journey; or sitting alone in a secluded place (one would not call a meditation hall or a bus station a secluded place). Generally, monks would also refrain from carrying on correspondence with women, other than for matters pertaining to the monastery, travel arrangements, providing basic information, etc. When teaching Dharma, even in a letter, it is easy for inspiration and compassion to turn into attachment.

Teaching Dharma

The monk as Dharma teacher must find the appropriate occasion to give the profound and insightful teachings of the Buddha to those who wish to hear it. It would not be appropriate to teach without invitation, nor in a situation where the teachings cannot be reflected upon adequately. This is a significant point, as the Buddha’s teachings are meant to be a vehicle, which one should contemplate silently and then apply. The value of Dharma is greatly reduced if it is just received as chit-chat or speculations for debate.

Accordingly, for a Dharma talk, it is good to set up a room where the teachings can be listened to with respect being shown to the speaker. In terms of etiquette, graceful convention rather than rule, this means affording the speaker a seat which is higher than his audience, not pointing one’s feet at the speaker, not lying down on the floor during the talk, and not interrupting the speaker. Questions are welcome at the end of the talk.

Also, as a sign of respect, when inviting a monk it is usual for the person making the invitation to also make the travel arrangements, directly or indirectly.

Minor Matters of Etiquette

Vinaya also extends into the realm of convention and custom. Such observances, which it mentions, are not ‘rules’ but skillful means of manifesting beautiful behaviour. In monasteries, there is some emphasis on such matters as a means of establishing harmony, order and pleasant relationships within a community. Lay people may be interested in applying such conventions for their own development of sensitivity, but it should not be considered as something that is necessarily expected of them.

Firstly, there is the custom of bowing to a shrine or teacher. This is done when first entering their presence or when taking leave. Done gracefully, at the appropriate time, this is a beautiful gesture, which honours the person who does it; at an inappropriate time, done compulsively, it can appear foolish to onlookers. Another common gesture of respect is to place the hands so that the palms are touching, the fingers pointing upwards and the hands held immediately in front of the chest. This is a pleasant means of greeting, bidding farewell, saluting the end of a Dharma talk or concluding an offering.

Body language is something that is well understood in Buddhist cultures. Apart from the obvious reminder to sit up for a Dharma talk rather than loll or recline on the floor one shows a manner of deference by ducking slightly if having to walk between a monk and the person he is speaking to. Similarly, one would not stand looming over a monk to talk to him or offer him something, but rather approach him at the level at which he is sitting.

Good is restraint in body,

restraint in speech is good,

good is restraint in mind,

everywhere restraint is good;

the bhikkhu everywhere restrained

is from all dukkha free.”Dharmapada

no. 361

Extract from: The Theravadin Buddhist Monk’s Rules – compiled and explained by Bhikkhu Ariyesako.