A History of Bodh Gaya

by Venerable S. Dhammika

Just before the full moon day of the month of Vesakha in about the year 528 BCE, a young ascetic of noble birth, worn out by years of self denial, arrived on the outskirts of the small village of Uruvela nestled on the banks of the sandy Neranjara River. Many years later he described the scene that unfolded before him. “There I saw a beautiful stretch of countryside, a beautiful grove, a clear flowing river, a lovely ford and a village nearby for support. And I thought to myself; ‘Indeed, this is a good place for a young man set on striving’ “. He settled himself under the spreading branches of the a nearby tree and prepared to begin his meditation. Just then a young woman named Sujata happened to be passing and noticing how thin he was, ran quickly home and brought him a bowel of milk rice and sweet honey. Strengthened by this nutritious meal the ascetic began his meditation. All night he sat there as the leaves of the tree quivered in the gentle breeze and the moon shone bright in the velvety black sky. Eventually the clouds of ignorance dissolved and he saw the Truth in all its glory and splendour. He was no longer Prince Siddhartha or the ascetic Gotama. He had become the Awakened One, the Compassionate One, the Light of the World, the Buddha Supreme. The Buddha spent the next seven weeks near Uruvela experiencing the bliss of enlightenment and moving to a different location every seven days. Then he set off for Sarnath near Varanasi to proclaim to the world the profound and liberating truths he had realised. Some months later, back in Uruvela again, he met three old ascetics with matted hair of the type that some Hindu swamis still wear, the brothers Nadi Kassapa, Gaya Kassapa and Uruvela Kassapa. Although revered teachers themselves they had never heard such wisdom as they did from the Buddha’s lips nor had they ever experienced the serenity and joy that showed so clearly on his smiling face. The three brothers, followed by their thousand disciples, bowed at the Buddha’s feet and asked him to ordain them as monks. This done, the whole party with the Buddha at its head set out for Rajgir. There is no evidence that the Buddha ever returned to Uruvela. But as his teachings spread and attracted more followers some of these people began to want to see the place where their teacher had attained enlightenment. Understanding that this could arouse faith or further nourish faith already aroused, the Buddha encouraged such visits. Thus the Buddhist tradition of pilgrimage began. By the 2nd century BCE the name Uruvela fallen into abeyance and the village came to be known as either Sambodhi, Vajrasana or Mahabodhi. The name Bodh Gaya only came into use in the 18th century.

There are records of pilgrims coming to Bodh Gaya from all over India and from almost every land and region where Buddhism spread. In the 11th century Acarya Dharmakirti from Sumatra made a pilgrimage to Lumbini, Kapilavatthu and Bodh Gaya. When I Tsing was in Bodh Gaya in the 7th century he met a monk who had come all the way from what is now Kazakhstan. Vietnamese began coming to India on pilgrimage soon after the introduction of Buddhism into their country in the 6th century. One of the earliest such records concerns two monks, Khuy Sung and Minh Vien, who took a ship to Sri Lanka, sailed up the west coast of India and then went from there by foot to the holy land. The two companions reached Bodh Gaya and then continued on to Rajgir where poor Khuy Sung died. He was only twenty five years old. In about 402 CE, after an epic journey through the mountains and deserts of Central Asia, the gentle and pious Fa Hien reached Bodh Gaya , the first Chinese monk ever to do so. On returning home he wrote an account of his pilgrimage which in later centuries inspired hundreds of others to follow in his footsteps. The most famous of these was Hiuen Tsiang who stayed in India from 630 to 644 visiting Bodh Gaya at least twice during that time. He too wrote an account of his pilgrimage in which he included much detailed and accurate information about Bodh Gaya. In fact, we today are able to identify many locations in and around the Mahabodhi Temple and know their histories and the legends associated with them, because of Hiuen Tsiang’s book. Another pilgrim, this time a Tibetan, who also bequeathed to us much information about Bodh Gaya’s past was the scholar monk Dharmasvamin. He arrived in the spring of 1234 only to find that “the place was deserted and only four monks were staying there. One of them said; ‘It is not good! All have fled from the Turushka soldiers’. The monks blocked up the door in front of the Mahabodhi Image with bricks and plastered it. Near it they placed another image as a substitute. They also plastered up the outside door of the Temple. On its surface they drew an image of Mahesvara to protect the Image from the non-Buddhists. One of the monks said; ‘We five dare not stay here and shall have to flee’. As the days stage was long and the heat great, they felt tired and as it became dark, they remained there and fell asleep. Had the Turushkas come they would not have known it”. The danger passed and Dharmasvamin and the other monks were able to come back. Dharmasvamin stayed for three months, went off to Rajgir and Nalanda and then returned to Tibet. His biography includes details of everything he saw and experienced in Bodh Gaya and is the last full account of the place until 1811.

The first evidence of a Sri Lankan coming to Bodh Gaya is an inscription by a monk named Bodhiraksita written in the 1st century BCE. This inscription is incidentally, also the earliest evidence of any pilgrim from outside India coming to Bodh Gaya. According to the Rasavahini a monk named Culla Tissa and a group of lay pilgrims made their way Bodh Gaya in about 100 BCE. King Silakala of Sri Lanka (518 -531) spent his youth as a novice in one of Bodh Gaya’s monasteries. The last Sri Lankan we know of to have visited Bodh Gaya until modern times came in the second half of the 15th century. This monk, named Dharmadivakara, went to Bodh Gaya and then decided to go on from there to Wu Tai Shan in China. While at the sacred mountain he met some Tibetans who invited him to their country where he travelled and taught widely. However, the strain of several long years of travel, the strange food and the cold climate all proved too much for poor Dharmadivakara for we read that on his way back to Sri Lanka he disrobed in Nepal and later died in India. But Sri Lankans were not just enthusiastic about going to Bodh Gaya on pilgrimage, they also did much to make it a vibrant and thriving centre of Buddhism. When, during the first half of the 4th century CE, the younger brother of King Meghavana (304-332) went on pilgrimage to India he found it difficult to get proper accommodation. On his return to Sri Lanka he mentioned this to his brother the king who decided to ask the Indian ruler for permission to build pilgrims’ rests at all the holy places. Permission was given to build one such establishment and thus the great Mahabodhi Monastery came to be built at Bodh Gaya on the north side of the Temple compound. An inscribed copper plaque above the door of this monastery announced that hospitality was to be given to everyone who came. It read, “To help all without distinction is the highest teaching of all the Buddhas”. In later centuries the Mahabodhi Monastery grew into a great monastic university on a par with Nalanda and Vikramasila and became the premier centre for the study of Theravada Buddhism in India. Buddhaghosa wrote both the Atthasalani and the now lost Nanodaya at this monastery before going to Sri Lanka. Other famous names associated with it include the Chinese monks Chin-hung and Hsuan-chao, the south Indian monk Dharmapala, author of the Madyamakacatuhsatika, and the Kashmiri Tantric siddha Ratnavajra. Tsami Lotsawa Sangye Trak is described in one ancient book as “the only Tibetan ever to hold the chair at Vajrasana” suggesting that he was a professor at the university. The last Therevadin monk whose name is mentioned in connection with the Mahabodhi Monastery is the Sri Lankan pundit Anandasri who subsequently lived and taught in Tibet. He is eulogised in one Tibetan book as “…foremost amongst the many thousands in the sangha of the island of Simhala, a disciple of Dipankara, residing at Vajrasana, a great scholar… skilled in two languages, one who seeks the benefit of the sangha, the excellent one”. As Anandasri was translating Pali text in the Land of Snows at the very beginning of the 14th century, it is likely that he was teaching at Bodh Gaya at least up to the end of the 13th century, proof that the university still functioned at that time.

Sri Lankans were also ready to help when the Temple needed repairs. A Tibetan work, the Mkhas-pa’i dga-ston, mentions a Tibetan yogi named Ugyen Sangge who, during one of his frequent trips to India, made contact with the king of Sri Lanka and repaired the Mahabodhi Temple with his help. This is said to have happened around the year 1286. The Mkhas-pa’i dga-ston also says that while the work was being done Ugyen Sangge stayed to the north of the Temple with 500 other yogis. This must be a reference to the Mahabodhi Monastery and its inmates and we cannot doubt that it was they who put Ugyen Sangge into contact with the Sri Lankan king in the first place and that they had a major role in the repairs. Given the Sri Lankan Buddhists’ deep regard for Bodh Gaya it is not surprising that it was yet again a Sri Lankan, Anagarika Dharmapala, who began the struggle to restore the Temple in 1893 and who build the first modern pilgrims’ rest at Bodh Gaya. Like the Sri Lankans the Burmese have long been coming to Bodh Gaya and on at least four occasions have renovated or repaired the Temple. In 1100 King Kyanzittha ” got together jewels of diverse kind and sent them in a ship with intent to build up the holy temple of Vajrasana, the great temple built by Asoka, which had fallen utter ruin. His Majesty proceeded to build it anew, making it finer than ever before” Three centuries later in 1471 King Dhammacetiya got “monks endowed with study and practice to embark at Bassein together with skilled masons, painters and builders, much treasure, royal letters written on gold under the authority of his seal and ambassadors of greater and lesser rank” and sent them to repair the Temple once again and to make offerings under the Bodhi Tree.

The main attraction for pilgrims at Bodh Gaya was the Vajrasana and the other six locations where the Buddha had stayed. Another attraction was the Mahabodhi Image, a statue in the Mahabodhi Temple that was believed to be an exact likeness of the Buddha himself. The legend concerning the origins of this famous statue is thus. When the Temple was built it was decided to enshrine a statue in it but for a long time no sculpture good enough could be found. One day a man appeared saying that he could do the job. He asked that a pile a scented clay and a lighted lamp be put in the Temple sanctum and the door be locked for six months. This was done but being impatient the people opened the door four days before the required time. Inside was found a statue of great beauty, perfect in every detail except for a small part on the breast that was unfinished. Sometime later a monk who slept in the sanctum had a dream in which Maitriya appeared and said that it was he who had made the statue. The Mahabodhi Image was the most revered statue in the Buddhist world and is mentioned in records for nearly a thousand years. The main temples at both Nalanda and Vikramasila had copies of this statue in them. When the Chinese envoy Wang Hiuen Ts’e returned home in the 7th century with a model of the Mahabodhi Image he was swamped with requests by people wanting to make copies of it. When the great Bengali pundit Atisa was in Tibet in the 11th century he sent a message back to Vikramasila in India asking that a painting of the Mahabodhi Image be made and sent to him. A Buddha statue the same dimensions as the Image is enshrined in the great stupa at Gyantse. The measurements for this copy were obtained from Sariputra, the last monk from Bodh Gaya when he was passing through Tibet in 1413. The Tibetan Tantric siddha Man-luns-po mentions seeing the Mahabodhi Image when he was in Bodh Gaya in 1300 and another pilgrim, Jinadasa of Parvata, came and worshipped it some time during the 15th century. But after that we here no more of it. The statue now on the Vajrasana inside the Mahabodhi Temple was found in the ruins and placed there by Cunningham in 1880. It dates from about the 10th century.

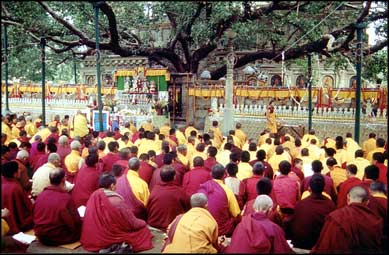

There were also colourful festivals to attract pilgrims. The most important of these was at Vesakha in May when people would worship the Bodhi Tree. Hiuen Tsiang wrote, ” On this day princes , monks and lay people come of their own accord in myriads to the Bodhi Tree and bathe it with scented water and milk to the accompaniment of music, flowers are offered and lights are kept continually burning”. The Kathina festival at the end of the rainy season in October went for seven days and attracted large numbers of monks and nuns, while the third festival was an exhibition of relics. When pilgrims returned home they wanted of course to take souvenirs and mementos with them. Several small models of the Mahabodhi Temple made of stone have been found which are thought to have been made for the pilgrim trade. Another popular souvenir were seeds and leaves from the Bodhi Tree. A 13th century inscription from Pagan in Burma mentions pilgrims returning from Bodh Gaya with such seeds. The Chinese monk Kwang Yuen returned from India in 982 with several leaves and in 1009 an Indian monk arrived at the Chinese court and presented the emperor with several leaves from the Bodhi Tree and an impression of the Vajrasana.

The popularity of pilgrimage gave rise to a whole body of literature, mainly stutras praising the holy places and exhorting the faithful to visit them. There were also mahatyaya or guide books to help pilgrims find there way and to inform of the times of particular festivals. The 14th century Tibetan scholar Jamdun Rigpel Rilti is said to have written a guide book to Bodh Gaya but unfortunately this work is now lost. Ancient Buddhist maps always showed either Mount Meru or Bodh Gaya in their centre. The most famous of these is the Gotenjiku Zu, Map of the Five Indias, drawn by the Japanese monk Juaki in 1364. This map is based carefully on Hiuan Tsiang’s account of his pilgrimage to India and indeed even marks his route with a red line. Mount Meru and Lake Anotatta with the traditional four rivers flowing out of it is shown in the centre while Bodh Gaya is located towards the southeast The purpose of maps like the Gotenjiku Zu was didactic and scholarly rather than practical but route maps meant to be used by those going to India existed too. One of the few such maps that survives, from northern Thailand, was drawn in the 19th century although based on a much earlier prototype, probably by someone who had actually been to India. The map shows important pilgrimage sites like Rajgir, Kusinara, Campa and Dona’s stupa, and gives their direction and the number of days needed to reach them from the Mahabodhi Temple, which is depicted in the centre of the map.

It is widely believed that Bodh Gaya’s temples and monasteries were destroyed soon after the Muslim invasion of India in 1199. There is no evidence to support this belief. On the contrary, records show that Bodh Gaya continued to function as a centre of Buddhist scholarship and pilgrimage up to at least the beginning of the 15th century. When Dharmasvamin came in 1234 there were still 300 Sri Lankan monks in the Mahabodhi Monastery. Shortly before his visit some Muslim soldiers had tried to steal the gems from the eyes of the Mahabodhi Image but this seems to have been just a part of a brief smash and grab raid that did little other damage. Twenty eight years later King Jayasena donated some land in trust to Mangalasvamin, the abbot of the Sri Lankan monastery. In 1298 a party of Burmese came to make offerings at the Bodhi Tree and to repair the Temple. They were helped in what they did by the resident monks. If you look at the paving stones on the floor inside the Mahabodhi Temple you will notice some have inscriptions and drawings on them. These were made between 1302 and 1331 by groups of pilgrims from Sindh. At the beginning of the 15th century Cingalaraja repaired some of Bodh Gaya’s shrines with the help of a monk named Sariputra and shortly after this an embassy from the emperor of China arrived with a letter for Sariputra, inviting him to visit that country. Records mention Sariputra passing through Katmandu in 1412 and Gyantse in Tibet the following year. This is the last mention until the 19th century of monks actually residing at Bodh Gaya although a trickle of pilgrims kept coming. In 1427 the Indian Tantric siddha Vanaratana planned to go to Bodh Gaya to erect a statue of his teacher but fear of being attacked by bandits made him cancel his trip. There is no doubt that Bodh Gaya endured at least two attacks by Muslims but the monks survived these and continued with their meditation and study. However with the stream of pilgrims gradually drying up and royal patronage no longer forthcoming, staying at Bodh Gaya became increasingly difficult and one by one the monks and nuns drifted away and Bodh Gaya was deserted.

Sometime in perhaps the 16th or 17th centuries a Hindu swami settled down near the crumbling Mahabodhi Temple and being ignorant of the true identities of the Buddha statues scattered around, began worshipping them as Hindu gods. This swami’s successors , the Mahants, eventually became powerful and wealthy and began to look upon the Mahabodhi Temple as their private property. In 1877 the king of Burma received permission from the British Government to repair the Mahabodhi Temple and soon after sent a large delegation of officials and craftsmen to do the work. Knowing nothing of archaeology these Burmese did enormous damage and destroyed much important evidence about the Temple’s history. Finally, at the insistence of Alexander Cunningham, the then Director General of the Archaeological Survey, the government intervened and did the job at a total cost of 100,000 rupees. In 1891 a young man named Anagarika Dharmapala came to Bodh Gaya to worship the place where the Buddha had attained enlightenment. He expected to be inspired and uplifted by such a holy place but all he saw were greedy brahmins nagging him for money and local people using the Temple compound as a toilet. He was deeply shocked and being of strong faith and abundant energy he then and there conceived the audacious idea of restoring Bodh Gaya to its former glory. This immediately put Dharmapala on a collision course with the Mahant and his minions. Until his death in 1932 he struggled on, often alone, through physical attacks and court cases, despite reversals and disappointments, but never lost sight of his noble goal. Finally in 1949, mainly due to the efforts of Mahabodhi Society, the organisation Dharmapala had founded to continue his work, the Bodh Gaya Act was passed, making provision for the setting up of a committee of four Hindus and four Buddhists to manage the affairs of the Temple. Even today this arrangement is far from satisfactory and is still the cause of problems which can only be resolved when Buddhists alone administer the Temple built on the spiritual and geographical heart of their religion.